British Airways Concorde in 1986.

The iconic supersonic jet, Concorde, (which probably had an even more iconic flight number: BA001) concluded its 27-year service with a final landing at Filton runway in November 2003. An absence of commercial viability, public concerns about the plane’s noise ( the sonic boom ) alongside high levels of pollution, led to its demise.

Concorde, which was a collaborative effort between Britain and France, reduced flight duration drastically. However, only a total of 20 Concordes were built – only 14 were used for commercial purposes. The remaining six were prototype, pre-production, and developmental models. These 14 aircraft made 500,000 flights since its first transatlantic crossing in September 1973. Travelling at a speed faster than sound, the supersonic jet flew over 2.5 million passengers to their destination.

A Triumph of Engineering for a Privileged Few

Concorde had a maximum speed exceeding Mach 2. Concorde had double delta wings, a configuration that pushed its aerodynamic capabilty.

Queen Elizabeth II and her husband, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, disembark from a British Airways Concorde supersonic transport aircraft upon their arrival for a royal visit.

However, only a privileged few could aboard the aircraft. As far back as 1976, a one-way ticket across the pond on the Concorde cost £431 [ approximately£2,200 ($2,800) adjusted to inflation]. It was also said that “Air France staff oozed élan,” at the Concorde lounge at JFK, which still ranks as one of the busiest airports in the US. The aircraft had only a hundred seats, though.

The perception of the Concorde was, was quite different from what it was really like, said Su Marshall to the CNN:

“For a girl used to flying steerage, once through the doors of the sleek, tiny, cigar tube into the body of Concorde, I knew I had entered into the rarified air of gods and kings. But dang, things were small and cramped. Leather, polish and flutes of never-ending Champagne, but really squished..But hey, three and a half hours to Paris? I sucked it up”

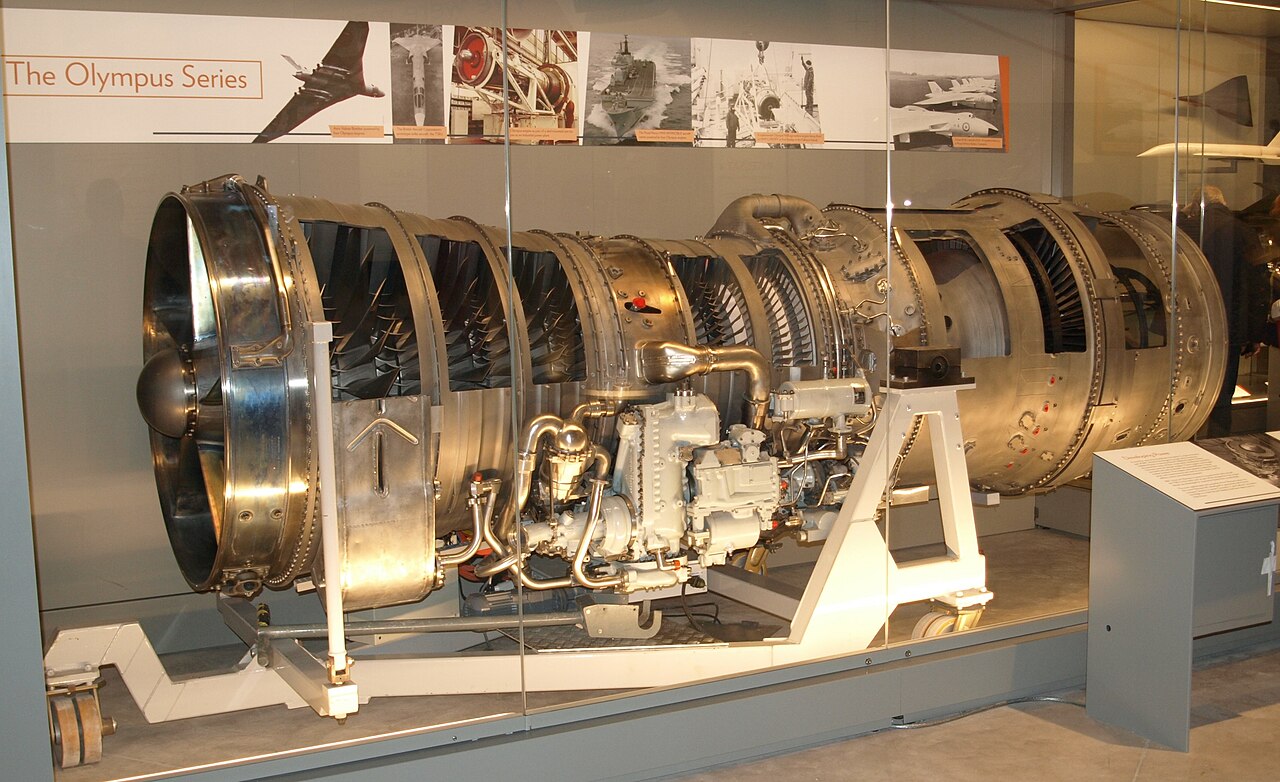

Concorde still holds the distinction of being the sole passenger aircraft that had turbojet engines with afterburners. Former British Airways Concorde captain John Tye, talked to CNN about the fact that “reheat” could increase the thrust of Concorde’s engines by as much as 20%:

“Concorde was vastly different from subsonic aircraft at the time. It had no flaps or slats (high-lift devices on the wing) and always used full power with reheat for takeoff….Each takeoff was a phenomenal experience, the performance such that we had to warn the passengers in advance what to expect. The roar of the Rolls-Royce Olympus engines, combined with being pushed back into your seat, was like no other civilian aeroplane.”

Rolls-Royce/Snecma Olympus 593, an Anglo-French turbojet

The Environmental Shadow of a Supersonic Jet

Behind the opulence and engineering of Concorde were more harmful emissions like nitrogen oxides (NOx) and CO2 compared to subsonic planes of its time. We have already touched upon how the aviation community had come up with Flygskam, a concept that was to alarm people of the carbon footprints associated with aviation. Perhaps associated movements such as Tagskryt would have been much more potent if the Concorde was still flying to this day.

Tågskryt: Was it Just A Social Media Trend Against Aviation?

Concorde produced three times more noise than other aircraft of its time. Its NOx and CO2 emissions were three times greater than today’s subsonic planes. Due to the exceptional heights that it flew in (it cruised at twice the height of a commerical jet), It contributed five times more to global warming.

NASA reports about the scale of pollution if supersonic aircraft operated regularly:

” In the scenarios with unrestricted flight paths, we find fleets of 130–870 commercial supersonic aircraft operating between 100,000 and 750,000 round-trip flights annually, thereby serving up to 2.5% of the expected global commercial seat-kilometers. This would result in a net increase of fuel burn from commercial passenger aviation by up to 7% and of NOx emissions by up to 10%…”

Concorde formation flight with the Red Arrows at the Queen’s Golden Jubilee.

The Concorde could cruise at an altitude of almost 18 kilometers. This is an altitude where you can find the ozone layer, and many feared that losses of the ozone layer would be greater. A report from the World Meterological Organization claimed that one-tenth of the total ozone column would be depleted if supersonic aircraft such as the Concorde entered mainstream. The chief scientist for Earth sciences at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Paul Newman, was quoted in Space.com to have commented:

“New supersonic and hypersonic aircraft are being developed that can release water vapor and nitrogen oxides into the stratosphere,” “At this point, there are not enough of them, but in the future, if you began to fly thousands of these aircraft in the stratosphere, it could have a significant effect.”

While we do know that NASA has tested hypersonic aircraft, the effect might be largely negligible as these didn’t fly for the same duration (or as frequently) as the Concorde did.

In Pictures: Aircraft Used In The North American X-15 Hypersonic Program

Nonetheless, the WMO report claimed:

“Future commercial supersonic or hypersonic aircraft fleets would cause stratospheric ozone depletion. Both types of aircraft would potentially release substantial amounts of water vapor and nitrogen oxides (NOx) into the stratosphere, with concomitant strong effects on stratospheric ozone arising primarily through enhancement of NOx catalytic ozone destruction at cruise altitudes. This could reduce total column ozone by as much as 10%, depending on aircraft type and injection altitude, and would be most pronounced in the Northern Hemisphere polar region in spring and fall.”

Research also revealed that Concorde’s engines emitted significantly higher quantities of sulfuric acid particles than the exhaust produced by subsonic aircraft. These sulfuric acid particles were subsequently determined to be a contributing factor in the depletion of the ozone layer. To examine the environmental effects of Concorde, David Fahey of the US government’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Boulder, sent a plane to chase the Conorde as “it flew high over the ocean near New Zealand, sampling exhaust gases in Concorde’s slipstream 10 minutes after the supersonic airliner had passed“. It was found that Concorde produced much more exhaust particles than expected.

Fahey also found that operating 500 aircraft (with exhaust) like the Concorde would increase the depletion of ozone by 2%, which would inturn increase worldwide incidences of non-melanoma skin cancer by 2%.

The Future of Supersonic Travel: A Balancing Act

A potential solution to operating the Concorde would be utilizing alternative fuels, such as the Sustainable Air Fuel (SAF).

NASA’s X-59, its quiet supersonic research aircraft, sits on the ramp at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California.

The future of supersonic travel hinges on the industry’s ability to address environmental concerns. There is a renewed interest in supersonic travel though, with Boom Supersonic’s Overture and NASA’s X-59 program exemplifying this trend. However, some critics are sceptic. One such name is Jeff Miller, the vice-president of Aerion, a US startup which “has already received over $100m in investment to design an A-S2 supersonic business trijet with Airbus“:

” My understanding is that the newest supersonic designs being developed would fail Icao’s subsonic CO2 standard by a wide margin.It takes a lot of energy to acceler..ate and then operate an aircraft at supersonic speeds. On an real-world basis, I’d expect even improved supersonic aircraft to be twice – or even more – carbon intensive than a modern subsonic aircraft. Speed kills.”

Only time will tell how polluting the supersonic aircraft of the future will be.

NASA’s X-59 First Flight, 2024