Photo: Ivan G. Somlai

While the Lukla Airport is known as the Hillary Airport (with the name of the other mountaineer first to Everest- Tenzing – often thrown in the mix as ‘Tenzing Hillary Airport’), it’s often news to a lot of people that this wasn’t the first (or the only) airport Sir Edmund Hillary had built in the Khumbu region.

Had his first attempt at building an airstrip/aerodrome/STOLport or whatever specification might be required to convey the sense of landing spot for an aircraft at such perilous, precarious, and limited runway been successful or passed the test of longevity, it (Mingbo Airstrip) would have been the airport located at the highest altitude. The Mingbo airstrip would, without a shadow of a doubt, also be the “world’s most dangerous airport” and perhaps one of the cheapest airstrips ever constructed.

Where is the Mingbo airstrip located? How was it made?

The Mingbo airstrip is located at an altitude of around 4650 meters/ 15,000 ft, at the base of Ama Dablam mountain. In comparison, the Lukla airstrip is only around 2700 meters high. Hillary said that it had taken around $900 to construct the Mingbo airstrip.

Photo: Vyacheslav Argenberg | WIkimedia Commons

Much of this cost was down to labor charges paid to the local Sherpas, who, in addition to the labor, had used their ancient knowledge of moving large boulders to clear land for the runway. Hillary and his team of mountaineers had tried to use sledgehammers to break down boulders present in the Mingbo airstrip. But the heavy rocks were impervious to such blows. It was the locals of the Khumbu region who used their ingenuity to move the large rocks.

Sherpas had dug craters right next to the boulders. They then used long sticks as levers to get the rocks into the large holes they had made. After the boulders had been cleared up, the Sherpas leveled up the airstrip.

Photo: Pasang Chhiki Sherpa

Why was the Mingbo airstrip made?

Around the time of the construction of the Mingbo Airport, a lot of Tibetan refugees (80,000 or so) had flown to Nepal through the Himalayas (of the Everest region and beyond) as they were being persecuted by the Chinese. It was during the Tibetan Uprising of 1959 that the 14th Dalai Lama crossed over to India. The tragedy of the subsequent Tibetan refugees has been captured in Tenzin Tsundue’s poems:

“Tell me what you have in your flute?

Is it the soft moaningOf a young girl, at 16

Thrown out of her house

Now living in the public park

Behind the toilets?

Or is that the breathing of the little boy

Who is tired and sleeping

At the police station?”

We might not truly know the scale of the misery of Tibetans who fled to the Khumbu region, as most of the Tibetan refugee poetry, like that of Tsundue, was written in India. Nonetheless, Sir Edmund showed solidarity with the Tibetan refugees who arrived in the Khumbu region. His anecdote:

“Camped on the broad flat area below the village were thousands of Tibetan refugees who had escaped over the Nangpa La with all their yaks. Food for the yaks had quickly disappeared so the Tibetans had butchered the animals and hung the meat out on hundreds of lines to preserve it in the sun. It brought forcibly home to us the desperate situation produced by the Chinese invasion of Tibet.”

tries to capture the plight of the Tibetan refugees living in the Thame village of Khumbu.

Photo: JDrewes | Wikimedia Commons

The Pilatus Porter PC-6 that landed in the Mingbo airstrip brought a lot of essentials, such as food for the Tibetan refugees. The aircraft also carried the materials needed for the construction of a building at Khumjug Secondary School. Sir Edmund Hillary describes this in his book, “The View from the Summit”:

“Captain Schrieber had a Pilatus Porter aircraft with an outstanding high-altitude performance, but he didn’t know of any place to land in the Khumbu. I remembered the site I’d pointed out to Peter Mulgrew up the Mingbo valley, but warned Captain Schrieber that it was at 15,000 feet. This didn’t seem to worry him, and we agreed that, if I could devote expedition effort to clearing the Mingbo landing strip he, in return, would fly in several loads of aluminium sheets to build a school at Khumjung.”

“Mingbo Airport was built during the Yeti research expedition. Sir Edmond Hillary was the team leader. After many months, the expedition left the Mingbo area. Pilatus PC-6 Porter (a small plane) landed there. I recall bringing food, medicine, mail, etc., from time to time. At the same time, Sir Hillary planned to build Khumjung School, and at the end of the Expedition, the PC-6 Porter brought school equipment to Mingbo airport, and Local people carried it down to Khumjung. There were many Aluminum sheets, and we built the first Himalayan Trust school from those materials in 1961 Khumjung. This is what I heard from elderly and I remember the school being constructed. We sat next to a big rock and our class started in an open place. I was in the first group of 35 , 40 Children.”

The role of the Silver Hut Experiment group in the construction of Mingbo Airport

In addition to the local Sherpas, the members of the Silver Hut wintering group were instrumental in constructing the Mingbo airstrip:

“So at my request, the Silver Hut wintering group put a team of men on to levelling the site at 15,000 feet, chopping off the frozen clumps of snow grass, filling in the worst of the holes, and rolling away the large boulders. Snow sometimes restricted their activity but it rarely lay for long once the sun was shining again. When the strip had been cleared to 400 yards the first landing was made….Work on the strip continued for some months and we finally enlarged it to 500 yards and generally improved it..”

Photo: Ivan G. Somlai

James S. Milledge, who was a part of Silver Hut, in his talk at the NATO Conference on Mountain Medicine in 2006, gave glimpses of the reason why the Silver Hut experiment was carried out:

“The idea was to study the long term effect of really high altitude on human lowland subjects. Our program of research included numerous studies in ourselves as we acclimatized. ….. The project for which I was particularly responsible was on the changes in the chemical control of breathing with acclimatization. I was also involved in a large study of the ventilation, heart rate and cardiac output on exercise at various altitudes. This was especially Griff Pugh’s interest. I also did a project on the changes in the ECG with increasing altitude.”

James returned to Solukhumbu in 1964 as a part of Sir Edmund Hillary’s Second Schoolhouse Expedition, which was aimed at the construction of school buildings. James, however, was there alongside Dr. Sukhamay Lahiri and physiological ream to study the “differences between ourselves, lowlanders and Sherpa highlanders at a camp high above Lukla at 4880 m”. The results showed that:

“.. Sherpas had a much lower hypoxic ventilatory response than did lowlanders both at rest and exercise “

Photo Credit: Pasang Chhiki Sherpa.

The last flight at the Mingbo Airstrip

The Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal knew about the flights being conducted in the Mingbo region months after operations were carried out there. Hillary was reprimanded quite heavily for helping flights operate in an airport that was not approved by CAAN. As a result, he had to pay a fine of $60. Later, representatives from the governing body of aviation activities in Nepal got on board to inspect the airstrip. Hillary describes the experiences of the landing:

“It was quite turbulent as we made our approach towards the hill at the bottom of the Mingbo runway. As Captain Schrieber headed down there was a fierce sideways gust of wind and the aircraft started sliding towards the left- hand edge of the field. Captain Schrieber’s reaction was immediate – he just dropped the aircraft from thirty feet to land with a huge thud and then rolled upwards close to the rocks on the left-hand side where we stopped safely at the top. We were all severely shaken. The Civil Aviation gentleman staggered out of the aircraft and vomited noisily. “

After such an experience, the officials from CAAN decided, on the Mingbo airstrip itself, that no flights would ever be conducted to and from Mingbo ever again. When the official was told (by Hillary) that without a flight, it would take 17 days on foot to get to Kathmandu, the officer agreed on the final flight.

Some Reasons why the Mingbo airstrip wasn’t a viable option

Problems with acclimatization

So, although the idea of building an airstrip at Mingbo might have established it as one of the highest airstrips in the world, we should know that the Sherpas who occupy the highlands of Khumbu are, in some ways, have it in their genes to acclimatize at high altitudes a lot better. The Silver Hut experiment proved that conclusively.

Someone who has been to the Khumbu region knows that Namche Bazaar (3400 meters) is chosen as one of the places for acclimatization. A local even said that was an airport constructed in Syangboche airport (let alone Mingbo), tourists would have to trudge back to Namche (or to lower altitudes) to acclimatize. So, an airstrip at Mingbo would necessitate two to three days of trek back to Namche to acclimatize and then climb back.

When there was what the Nepali Times dubbed “an air war over Lukla” during the construction of the Syngboche Airport that would have allowed tourists to upwards of Namche Bazaar in a single flight and thereby save around 5 days of trek, Ang Tsering Sherpa, a resident of Khumjung and owner of a number of hotels along the Everest Base Cap trail was quoted to have said; “People will continue to fly into Lukla for acclimatization, maybe 40 percent will fly out of Syangboche.” Syangboche is located at an altitude of around 3700 meters; Mingbo airstrip was around 1000 meters higher and, therefore, would’ve proved to be a very difficult place in the Everest region to acclimatize.

The “funneling” effect at the Mingbo Airstrip

There’s another reason why the Mingbo Airstrip wasn’t a viable option. In a study that looked at 12 years of flight in the Everest region conducted by the retired captain of Royal Nepalese Airlines, Emil J. Wick, and Edward E. Hindman of The City College, New York, there have been reports of a “funneling effect” that allowed the Pilatus Porter operating in the Everest region to soar above the ceiling altitude of the aircraft:

“Thc flight pattern followed the valleys, which were usually ncarly calm, until reaching Syaogboche airfield. There, a transition occurred to the high speed westerly airflows. As a result of the high-speed flows, two wake turbulence regions were often encountered. The first region was downwind (east) of Taboche peak and the second was downward (east) of the Chakri ridge. To avoid these regions, the plane flew underneath the wakes. ”

While mountain flights are currently conducted in Nepal, they go nowhere close to the mountains of the Everest region as the flights reported by Emil J. Wick above did. But the experiences of Captain Emil J. Wick, given his accounts in the report, which was presented at the XXI OSTMongress, Wicner-Neustadt’ Austria (1989), hint at times when he soared above some lofty mountains:

“Whcn possible, soaring flights were conducted between about 7.800m to 10,000m (Cu cloud base over Lhotsc). … strong downdrafts were encountered immediately downwind of the southeast and west ridges of Everest. The rising motions on the face of’ Lhotse rcvcal a “funnelling” effect … and the downdrafts reveal sinking air in thc ice of Everest- The “funnclling” effect was not predicted from initial Everest flow simulations..”

The possibility of the formation of Mountain Waves

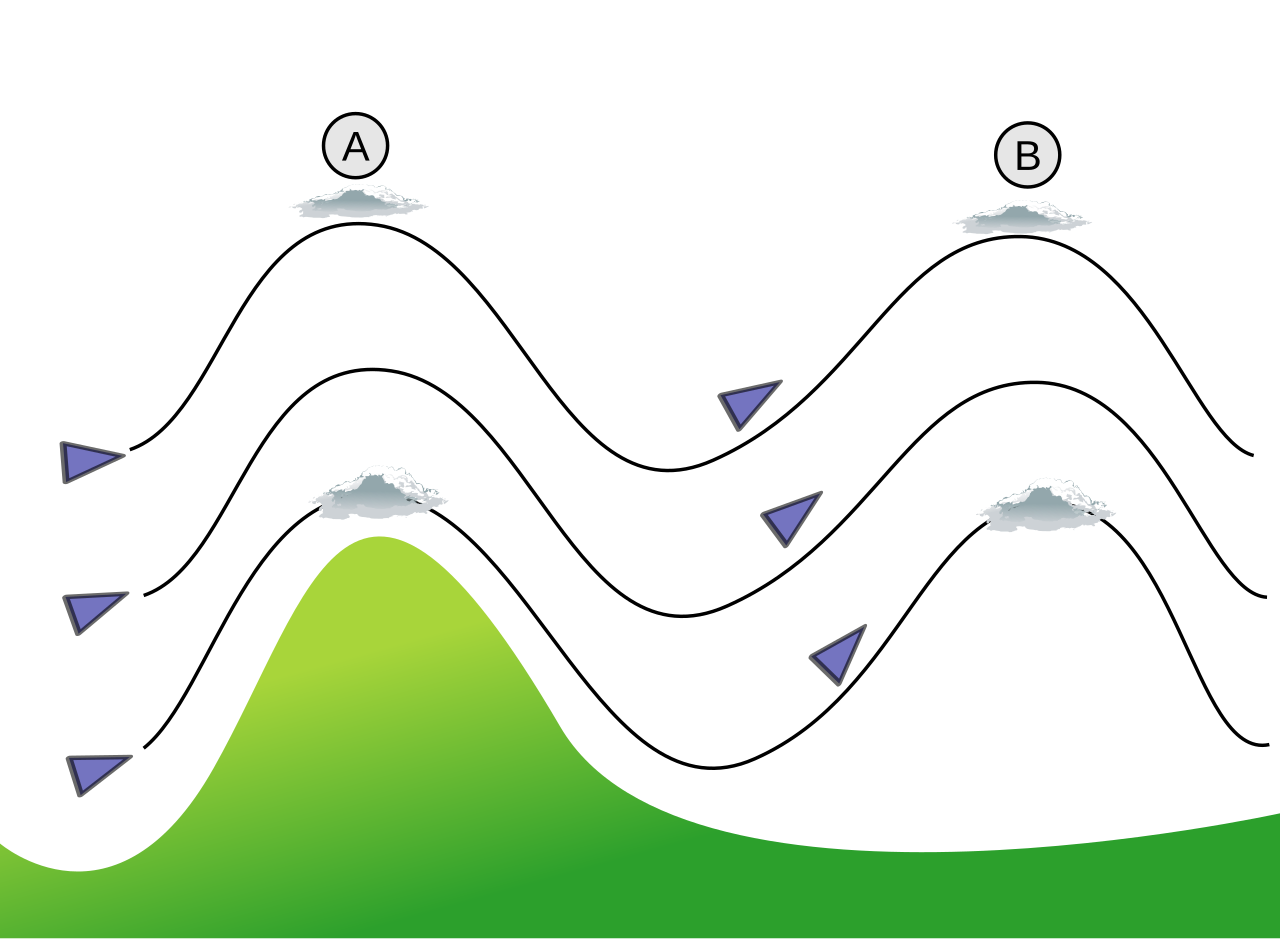

Although there is limited literature related to what the retired Captain of Royal Nepal Airlines Emil J. Wick described as the “funneling effect,” the possibility of mountain waves being formed in the Mingbo airstrip-like conditions is well-documented in the aviation community.

Photo: Dake | Wikimedia Commons

Mountain waves are formed when the horizontal airflow is disrupted by high mountains, creating rotors that can cause aircraft to lose control. In a report published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the dangers of mountain waves are clearly written:

“As winds become stronger aloft, mountain wave turbulence will develop more often and may cause significant damage to the structure of aircraft and result in loss of control. General aviation pilots may also experience greatly reduced climb rates due to severe downdrafts generated by mountain waves. Because of their life-threatening effects, it is important to understand the often unseen hazards attributed to mountain wave turbulence… “

Mountain waves are also known as atmospheric gravity waves. These waves are known to affect aircraft performance in other ways, too, as they contribute to cloud formation and microbursts. Such waves are known to produced turbulence even in clean air, leading to some flight disruptions. Binod Adhikari, a researcher of space science and the Head of Department of Physics at St. Xavier’s College, Nepal commented about some difficulties in operations of flights in the Mingbo airstrip:

“While gravity waves are a natural part of atmospheric dynamics, they can create challenges for aircraft operations, particularly in regions with strong wave activity like the Eevrest region. Microbursts are intense downward bursts of air that can occur near mountains or during thunderstorms. Microbursts are a type of wind shear and can pose a significant risk to aircraft during approach or departure from airports in mountainous regions. This type of turbulence occurs at high altitudes where there are no visible clouds. There’s also the possibility of Clear Air Turbulence (CAT) at the Mingbo Airstrip. CAT can be caused by wind shear, jet streams, or atmospheric instability. It can result in sudden jolts or bumps experienced by aircraft, potentially causing discomfort for passengers .”

Photo: Mr. Glen Talbot | Wikimedia Commons

But mountain waves are not always doom and gloom. They are known to aid in glider operations, often taking aircraft to altitudes that wouldn’t normally be achievable. The “Airbus Perlan Mission II” project rose to heights of more than 76,000 ft—almost double the height reached by Captain Emile J. Wick. But unlike the PC6, the Perlan II was specifically designed to glide. The Perlan II project achieved this height, taking advantage of the mountain waves generated in the El Calafate region in southern Argentina.

But not every aircraft (or pilot) is able to cash in on the record-breaking possibilities of mountain wave glide. Predictions of the formation of mountain waves’ gliding conditions are down to sophisticated scientific instrumentation and analysis. This is something that is lacking in Lukla/Mingbo/Syangboche airstrips. And the prediction of weather despite state-of-the-art instruments can prove to be difficult, which is why the NOAA cautiously says:

“While optimal mountain wave turbulence has helped glider pilots attain record high and long-lasting flights, when it is unexpected, it can be deadly. As with any flight, situational awareness of the enroute environment is key. Mountain wave turbulence adds one more level of complexity to those flying along or downwind of tall peaks and mountains from the fall through the spring seasons.”

Fuel Freeze is likely at Mingbo Airport and other high-altitude airports in Khumbu

A scenario extremely likely to develop during a flight to an airstrip like Mingbo is the possibility of fuel freeze. When the crash of British Airways Flight 38 led to the first-ever hull loss of a Boeing 777, the air crash investigation reported that the development of ice crystals in the jet fuel was to blame. We can’t be sure that such ice crystals won’t develop at Mingbo when the temperature at this airstrip persistently touches down below zero degrees centigrade.

Fuel freeze also caused a most glaring crash of one of the biggest aircraft ever made– the An-124. In December 1997, the aircraft carrying Sukhoi Su-27UBK fighters for delivery to Vietnamese forces crashed after taking off from Irkutsk, killing 23 people on board and 49 people on the ground, leaving 70 families homeless. Although the cockpit voice recorder had been too heavily damaged to aid in the investigation, the possibility of mixing regular jet fuel with cold weather fuel might have been a cause. Itkutsk was -20 degrees cold when the aircraft took off. Mingbo gets as cold as Itkutsk.

Photo: Alexander Makarov | RIA Novosti archive | Wikimedia Commons

Whenever airstrips are made in a particular region, there’s an analysis of other strips of land nearby where an aircraft could make emergency landings. One of the more viable options for the emergency landing in the Khumbu region is at Synagboche Airport, which is quite cold as (if not colder than) Mingbo. Sygboche airport also cannot guarantee the possibility of jet fuel being frozen.

Aerodynamic and other constraints while flying aircraft to Mingbo airstrip

A careful analysis of the STOLports of Nepal reveals that a number of them possess a degree of acclivity: the slope of the Lukla airstrip is 11 degrees, and the RARA airport has a slope of approximately 7 degrees. The gentle upslope that aircraft encounter in these airports acts as a natural breaking mechanism, allowing aircraft to halt quickly. While taking off, the aircraft takes advantage of the natural thrust of gravity.

Photo: Airbus

However, other aerodynamic challenges are posed by STOLports, such as Mingbo and Lukla. Motiram Itani, an aeronautical engineer who worked at Himalayan Airlines and is one of the founders of a Part 147 school in Nepal, says there are multiple difficulties while flying to Mingbo. He recalled:

“ The Pilatus Porter PC6 Hillary took to Mingbo was a single-engine aircraft, but such aircraft are currently banned from flying passengers in the country. In a two-engine aircraft, there’s always another engine that can come to the rescue in case one fails. In the aftermath of the Air Kasthamandap crash, Nepal allowed only goods to be transported with single-engine aircraft.”

Possibility of Hypoxia while flying to Mingbo

When oxygen supplies are low in the tissues of the body, underlying diseases such as congenital heart defects, bronchitis, etc.(which are directly correlated to blood flow or breathing) can flare up. Functioning of the brain and heart can be impaired or damaged and could potentially lead to death.

FAA marks the causes of hypoxia as: “flying, non-pressurized aircraft above 10,000 ft without supplemental oxygen, rapid decompression during flight, pressurization system malfunction, or oxygen system malfunction.”

Regarding how hypoxia can be prevented, the FAA clearly directs:

“fly a well-maintained pressurized airplane or fly at an altitude where oxygen is not required….. If pressurization is not an option and supplemental oxygen is not available, limit your exposure time to less than 1 hour between 10K feet and 14K feet, including not more than 30 minutes between 12K feet and 14K feet. If you have supplemental oxygen, use it above 5K feet during night flights and above 10K feet during daytime flights.”

The Mingbo airstrip is located at an altitude of 15,000 ft. Clearly, pilots and other passengers who fly to such high altitudes are susceptible to hypoxia. Given that the weather in Mingbo is more unpredictable than in Lukla, we don’t know for how many days flights might be impossible to run from Mingbo if the weather gets awry. We have seen many passengers stuck in Manthali and Lukla airport for weeks, trying to catch a flight.

Hillary had memories of Mingbo Airstrip when an aircraft first landed in the Lukla airport

Hillary/ Tenzing Hillary/ Lukla Airport was constructed in the 1970s—a decade after the Mingbo airstrip had been functioning and had been scraped away. This airport is now dubbed the “gateway to Everest” and has a rather underserved epithet of “the world’s most dangerous airport.” When Hillary was waiting for an aircraft to land at the Lukla Airport (the flight was to determine if Lukla airstrip was a viable option), he had the unpalatable experience of landing at the Mingbo airstrip with the officials of the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal at the back of his head:

“ No doubt with memories of Mingbo airfield two Civil Aviation representatives were coming in as observers on the new airfield’s first flight and their judgement would be final. It was the sharp ears of a Sherpa who first heard the aircraft coming up the valley and we hastily removed all the children and cows off the runway. I admit to feeling rather tense as the Pilatus Porter circled overhead. Then the plane wheeled, its flaps came down and it swung in to the bottom of the strip. The wheels touched with a puff of dust and next moment it was rolling up the airfield and came to a rapid halt. It took full power for the plane to taxi to the top of the runway and then we were welcoming the clearly delighted crew and passengers. I had an enormous feeling of pleasure and relief. Lukla quickly became the busiest mountain airfield in Nepal and the gateway to Everest.”