Image: Simon Allardice from San Francisco, USA| Wikimedia Commons

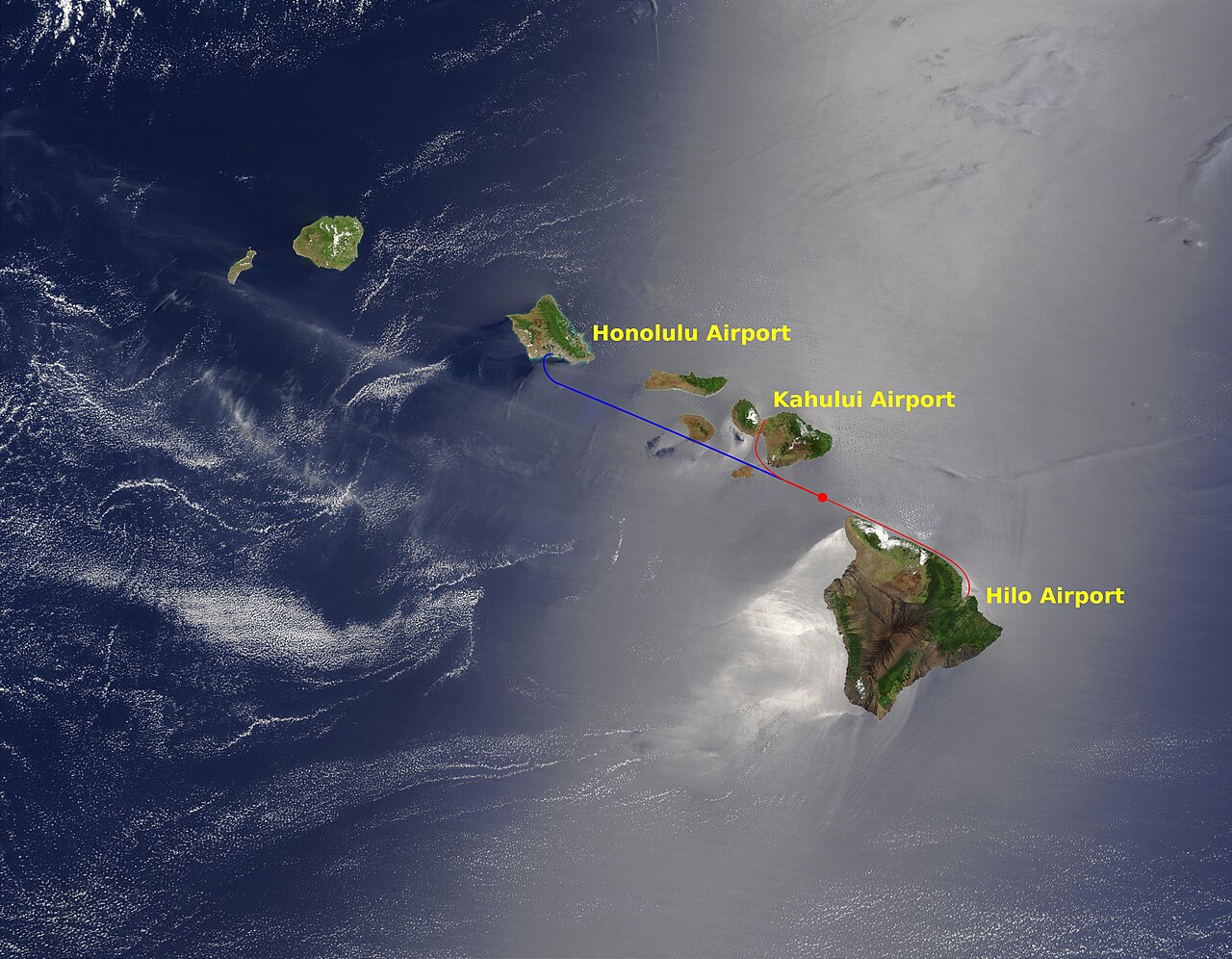

On 28th April 1988, Aloha Airlines Flight 243 was set to be a routine 35-minute inter-island flight in Hawaii. To put this into perspective, this duration is equivalent to the flight time to what is known as the most dangerous airport in the world, i.e., Lukla Airport, from Tribhuvan International Airport. The flight was scheduled to take-off (and it did) at 1:25 PM from Hilo to Honolulu and the aircraft in question [Boeing 737-297 (which was mnufactured in 1969 and had 35,496 airframe hours)] had already completed eight flights that very day by the time it was ready to take to the skies again.

Although a passenger had noticed a small crack in one of the riveted panels on the fuselage, she assumed it was innocuous. After all, a well-established airline undertakes mandatory Ab,B,C, and D checks of an aircraft to ensure its air worthiness. But 20 minutes after takeoff, as the plane reached its cruising altitude of 24,000 feet, the roof of the aircraft gave in and the aircraft was to limn against the firmament. This led to one of the most unforgettble incidents of the aviation industry, and perhaps one of the most shocking fatalities in all of aviation history.

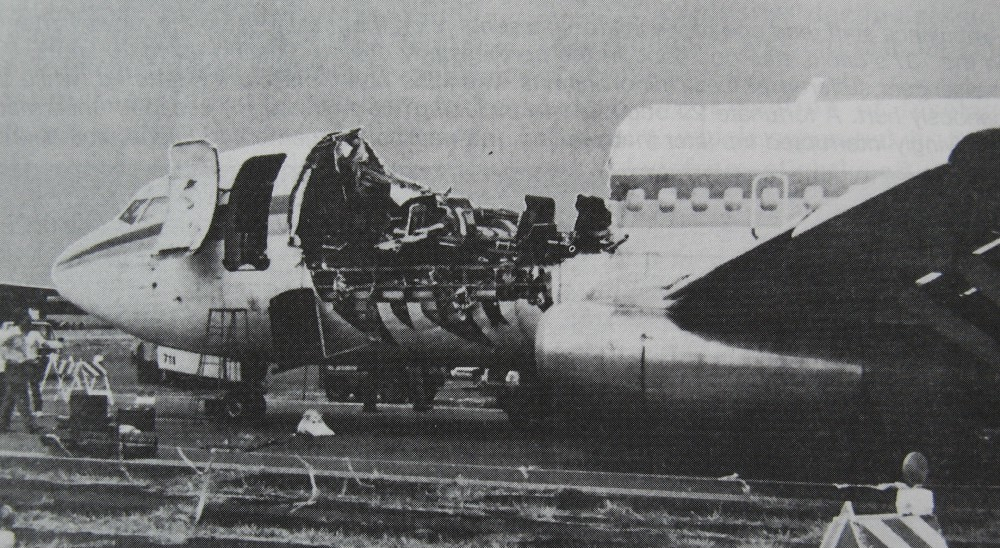

35 square meters of the fuselage tore off

One’s imagination might be tested if we are to imagine the frenzy inside the aircraft when with no warning, a massive section of the fuselage (almost twice the size of a cricket pitch) disintegrated mid skes and exposed the passengers to the open skies above. Decompression followed, leading people gasping for air at an altitude where oxygen is so thin that one might suffer from hypoxia. A near complete wiping out of the Oxygen masks and temperatures plummeting to -45°C made the situation as dire as it could get.

Image: Bob Linsdell | Wikimedia Commons

A flight attendant was blown out with the fuselage

Three flight attendants were onboard Aloha Airlines Flight 243:

-

CB Lansing: She was serving drinks near Row 5, was blown out of the aircraft (as the roof tore off). Her deceased body was never recovered.

-

Jane Sato: She was near Row 2 when the accident took place and was knocked to the floor and injured by luggage.

-

Michelle Honda: She was located near Row 15, and tried using the intercom to reach the cockpit but received no response. This prompted her to ask passengers, individually, whether they knew how to fly an aircraft. This only escalated the panic among the passengers. Although she did see Jnae bleeding, she couldn’t quite get a glimpse of what was happening inside the cockpit.

Exposed to wind and cold like in no other flight

Although passengers were exposed to violent winds approaching 500 km/h and temperatures of -45 degrees, the pilots [Pilot in command, Robert Schornstheimer ( experience of 8,500 flight hours, 6,700 of which were in Boeing 737s and first officer Madeline “Mimi” Tompkins (experience of 8,000 flight hours, 3,500 of which were in 737)]were infact alive, and in much better condition. After all, unlike the passengers, their oxygen masks were working quite well.

After the impact caused by the dismembering of a section of the fuselage, the two pilots turned around and noticed that the aircraft door and a sizable chunk of the aircraft’s roof had been lost. Following their observation, they decide to carry out an emergency landing, and begin descending the aircraft at a speed of more than 4000 ft per minute.

The asymmetry in the aircraft’s weight distribution following the loss of the roof also meant that the aircraft’s nose had dived almost a meter down from its regular alignment. There was a real possibility that the nose of the aircraft would be separated from the non-dismembered part of the aircraft.

First Officer Mimi Tompkins contacted Air Traffic Control in Honolulu to report the emergency. She was advised to land in Maui, which was closer. Almost three minutes after the roof had detached, Tompkins was in contact with the Maui Airport, which was alerted, and all emergency services (Firefighters, rescue crews, and ambulances) were mobilized.

By this time, aircraft was flying at 14,000 feet, almost nullifying the fears of hypoxia. The pilots steered the aircraft away from the danger posed by the 10,000 ft Haleakalā Summit, and headed towards the Maui Airport. However, they were unable to ready the nosewheel for landing, and had taken in considerations for a belly landing. However, a person observing the aircraft with binoculars at Kahului caught sight that the nosewheel was already in position, reading the aircraft for a normal landing.

Image: NASA | Wikimedia Commons

Aloha 243 miraculously had only one fatality

Thirteen minutes after the collapse of the 35 squared meter area of the roof, Aloha Airlines Flight 243 landed at Kahului Airport. Although most of them were safe, many of them sustained injuries:

- An 84-year-old female passenger [on seat 5A] had a skull fracture

- The passenger sitting in 6A suffered a broken hand.

- The passengers in 4A and 4F were seriously injured.

Passengers in Rows 4 to 7 had the most injuries as these were the seats over which the roof had blown apart. Passengers in Rows 8 to 21 were only minorly injured, while 21 passengers weren’t injured at all.

One of the biggest reasons why Aloha 243 escaped a greater fatality count was because the seatbelt sign was still on when the roof gave in. All of the passengers made their way from the aircraft from emergency exits.

Investigations revealed cracks in Aloha Airlines’ inspections

A Boeing 737’s fuselage is made of aluminum sheet metal panels arranged circumferentially in a frame, with each panel overlapping the other by 3 inches. The overlapping area is called the “Lap Joint”. As the thickness of these sheets was only 1 mm, Boeing developed a bonding process to allow the skin to absorb stress like a single unit by using a strong glue called Epoxy to join the different parts of the plane. When this glue dried, a strong bond developed to distribute the stress in all the plates and to prevent any cracks.

However, glue isn’t the only way that the sheets hold together. There were three rows of rivets on every overlap, too. The overlapping parts of every sheet were riveted together so that the entire frame of the airplane could be secured. Boeing’s first batch of 737s used this method to join the sheets.

However, problems such as the weakening of the bonds when exposed to moisture meant that the epoxy glue started degrading and the metal corrosion ensued. This meant that the stress on these sheets was borne by the rivets instead of the glue. As a result, Boeing decided to use “Hot Bonding” i.e., using heat and pressure to attach two sheets together, to bond the sheets together. The accident of Aloha Airlines Flight 243 had taken place 16 years after hot bonding had already been introduced in Boeing’s planes.

Much like how every accident in Nepal raises concerns about the use of old airplanes (as was the case in Yeti Airlines Flight 691), Aloha Airlines was blamed for still using an old plane. And some of the findings reveal this to be the case:

- In 1972, Boeing had issued a service bulletin stating that afore-mentioned possible problems may arise.

- In 1987, Boeing issued an Alert Service Bulletin that their older planes should be inspected and repaired accordingly in case any carriers hadn’t done so already.

Boeing also had a Safety Design stating that in case of a tear in the fuselage, it needed to be limited to a 10 inch by 10 inch square. While Tear Straps were placed at every 25 cm of the plane’s body, Flight 243’s condition was so terrible that even these tear straps didn’t come in handy.

NTSB recorded the probable cause of the accident in the following manner:

“The failure of the Aloha Airlines maintenance program to detect the presence of significant disbonding and fatigue damage, which ultimately led to failure of the lap joint at S-10L and the separation of the fuselage upper lobe. Contributing to the accident were the failure of Aloha Airlines management to supervise properly its maintenance force as well as the failure of the FAA to evaluate properly the Aloha Airlines maintenance program and to assess the airline’s inspection and quality control deficiencies.”

In addition, the investigation report also said that the contributory factors for the accident were:

“..the failure of the FAA to require Airworthiness Directive 87-21-08 inspection of all the lap joints proposed by Boeing Alert Service Bulletin SB 737-53A1039 and the lack of a complete terminating action (neither generated by Boeing nor required by the FAA) after the discovery of early production difficulties in the 737 cold bond lap joint, which resulted in low bond durability, corrosion and premature fatigue cracking.”

Cracks in an aircraft’s body are often detected by a process known as Eddy Currents technique i.e., the use of electric current through metal to detect microscopic cracks. Aloha Airlines was found to have not used this technique properly to find and repair cracks.